ENNIS Ethel 1956

Ethel Ennis, born (1932) and raised in Baltimore, is the essence of the "renaissance woman". Although an international jazz career takes up most of her time, Ennis devotes the remainder of it to community roles as a woman minority entrepreneur, a band leader, a cultural ambassador, and a civic activist.

Ennis' musical interests began at an early age. She began playing piano at age seven. It was a love that led to her first job in a local church. By fifteen, Ennis love of music had grown to encompass rhythm and blues as a complement to her gospel and classical roots. In the late 1940s, Ennis joined a jazz group led by Abraham Riley in an effort to cultivate her piano and vocal skills in this genre. During the 40s, Ennis displayed her raw talent by winning a number of small, localized contests. However, her career did not take off until her graduation from high school in 1950. At that time, Ennis began touring with a number of jazz and R&B artists that performed throughout the United States and London. She quickly went on to sing with everyone from Louis Armstrong to Duke Ellington to Count Basie. Nevertheless, it is Ennis' solo performances that may hold the most significance in her career.

In 1982, Mayor William Donald Schaefer appointed both Ennis and her husband, Earl Arnett, Cultural Ambassadors of the City of Baltimore. This honor would eventually take her, in 1987, to the First International Music Festival in Xiamen, China. Despite international acclaim and worldwide tours, Ennis has been able to avoid the trials and tribulations of fame by remaining in her hometown of Baltimore. Some critics cite this as a fault, but Ennis defends her choices in a biography entitled "Ethel Ennis: The Reluctant Jazz Star", written by Sallie Kravetz in 1984.

Remaining in Baltimore has enabled Ennis to take an active role in civic duties. She was nominated to the Hall of Fame of Frederick Douglass High School and received an honorary Doctor of Fine Arts Degree from the Maryland Institute College of Arts.

In recent years, Ennis has become involved in the award-winning children's program produced by the Maryland Department of Instructional Television called "Book, Look, and Listen" In 1984, Ennis opened "Ethel's Place" - her own music club located in Baltimore's cultural district across from the Meyerhoff Symphony Hall. A great success, the club actually broadcast live on public television across the country on New Year's Eve in both 1985 and 1987. Ethel performed with Joe Williams, Ray Brown and Milt Jackson, Phil Woods, Gerry Mulligan, Toots Thielemans, Wynton Marsalis, McCoy Turner, and Stephane Grappelli in these memorable broadcasts. In 1988, Ennis and her husband Arnett, made the difficult decision to sell "Ethel's Place" in order to "devote their creative energies to words and music." Ennis has survived and overcome many prejudices as a black woman, both in her professional and personal life. She uses her music as a weapon to combat prejudice and injustice throughout the world, by promoting love, compassion, and unity. Ennis refers to this power as "Soft Power", a "power within, the spiritual energy we all possess to change ourselves and the world around us." In this way, she believes music is not only a medium to be used for entertainment, but also a way to "inform and inspire."

A Hildner Productions cd "Ethel Ennis" came out in 1993. It celebrates Ethel’s first major recording in over 14 years. It consists of 11 jazz standard and contemporary songs in an exquisite chamber music style that highlights the musicality and phrasing that has made Ethel one of the luminary singers of our time. Ethel is accompanied by jazz master musicians Marc Copland and Stefan Scaggiari trading off on piano, Drew Gress on bass, and Paul Hildner on drums. Ethel shows her versatility and brilliance by accompanying herself on piano for the much loved hit “Something Cool.” Then came "If Women Ruled the World" in 1998.

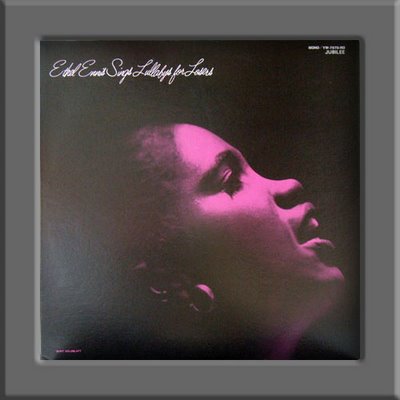

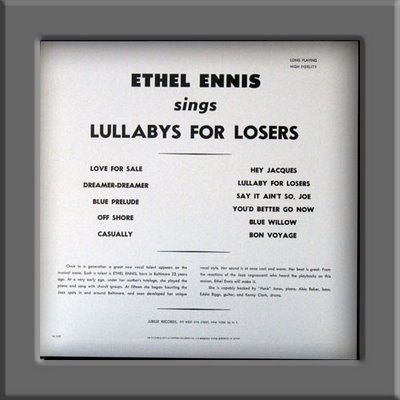

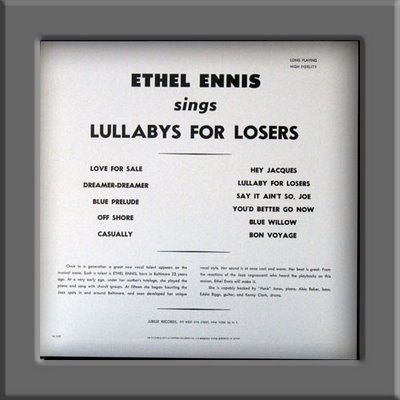

The is the first Ethel Ennis lp (mono recording) and you shouldn't miss it. At this time Ethel Ennis is only 23 years old !!! A wonderful voice capably backed by Hank Jones piano, Abie Baker bass, Eddie Biggs guitar and Kenny Clarke drums. (The lp is 50 years old... but plays very well)

Here, Geoffrey Himes from the Baltimore City Paper, tells us Ethel Ennis story...

At the end of her new cd "Ennis anyone?", Ethel Ennis tackles the old jazz standard “But Beautiful.” As is her wont, the Baltimore singer slows the tempo, even slower than the famous ballad versions by Nat King Cole, Bill Evans, and Billie Holiday. In her still-lustrous soprano, Ennis stretches out the melody and lyrics as if they were taffy, capturing the wistful realization that, even when it tortures us, love is beautiful in its way.

At the end of her new cd "Ennis anyone?", Ethel Ennis tackles the old jazz standard “But Beautiful.” As is her wont, the Baltimore singer slows the tempo, even slower than the famous ballad versions by Nat King Cole, Bill Evans, and Billie Holiday. In her still-lustrous soprano, Ennis stretches out the melody and lyrics as if they were taffy, capturing the wistful realization that, even when it tortures us, love is beautiful in its way.

But Ennis can’t stay serious for long. After Stef Scaggiari’s elegant piano solo, she murmurs, “As Billie would sing,” and launches into a spot-on impersonation of Holiday, full of throat-scraping purrs, that has the live audience at the Montpelier Cultural Arts Center in Laurel chuckling.

It’s a telling moment, for Ennis is probably the second most famous jazz singer to come from Baltimore. Ennis’ fame falls far short of Holiday’s, but the local legend has had a much longer and much more contented life than the international legend did, and that’s a trade-off Ennis is glad she made.

Ennis will forever be tied to Holiday by their shared hometown. But when she’s singing in her own voice, Ennis doesn’t sound all that much like Holiday. Ennis’ rounded, flush tone and bouncy phrasing more closely resemble her two biggest heroes, Sarah Vaughan and Ella Fitzgerald. And Ennis’ playfulness—her habit of breaking into impersonations, new comic verses, or impromptu patter in the middle of a song—is the diametric opposite of Holiday’s troubled-martyr persona. That playfulness may have cost Ennis a Holiday-like myth, but it has helped keep her sane.

“It bothers some people if an artist is just like them,” Ennis muses. “They don’t want Ethel the neighbor—they want Ethel the diva. They want their artists to be off in the distance somewhere on a pedestal. I never wanted to be on a pedestal. There’s not enough room to move around.

“I was never as famous as Billie, but I’ve definitely had a happier life, and I credit that to my grandmother and her teachings,” she continues. “I credit it to the musicians I worked with, because they took care of me; they didn’t take advantage of me. And I credit it to never leaving Baltimore to move to New York, even though people kept telling me I should. I’ve always believed you can bloom where you’re planted. You may not get wealthy or famous, but you can bloom.”

Ennis, now 72, grins broadly as she slouches on the couch in her brick rowhouse near Mondawmin Mall. Her hair is cropped close in a salt-and-pepper Afro; she wears a white sweater and black slacks and sports two diamond studs in each ear. Next to her on the couch is her husband, Earl Arnett, the former Sun reporter who defied Maryland’s miscegenation laws at the time to marry the young singer in 1967. They’ve lived in this same house ever since.

Not far from that house is the Gilmor Homes public housing project in Sandtown-Winchester, where Ennis grew up. In the 1930s and ’40s, when she lived there, housing projects were brand new and desirable. It was a tight-knit village, a breeding ground for such musicians as guitarist O’Donel Levy, keyboardist Charles Covington, and drummer Chester Thompson. Ennis herself took piano lessons so she could play at the Ames United Methodist Church when her mother had to take some time off.

“But we lived above a lady who threw house parties on weekends with red and blue lights,” Ennis remembers. “My grandmother thought it was terrible, but the music would come up through the floorboards from the apartment below, and I could really hear the bass lines. I remember hearing Lil Green singing, and that’s how I learned the blues.”

The Abraham Riley Octet, a bebop band in the Gilmor Homes, needed a pianist and invited the 15-year-old Ennis to join the band. One night at a Randallstown Odd Fellows Hall, with a stove in the middle of the floor, a customer offered Riley a big tip if Ennis would sing Lil Green’s “Romance in the Dark.” She had never sung in public before, not even in church, but the tip was too big to resist. She was only 15 and could only guess at what the suggestive lyrics hinted at, but a big, vibrant soprano that she never knew she had came pouring out of her mouth. The crowd went nuts, and she had to sing it again and again.

Soon she was singing all over town, eventually as a piano-and-bass duo with Montell Poulson. They played the Casino across from the Royal Theatre, Sherrie’s Bar in Highlandtown, the Zanzibar in West Baltimore, Phil’s in East Baltimore, and even the Oasis and the Flamingo strip clubs on the Block. Then she met George Fox, a short, round, 300-pound cannonball of a man who was literally a Damon Runyon character: Runyon had written about Fox’s exploits as a Times Square gambler in Manhattan.

After leaving Manhattan under shady circumstances, Fox ended up with a nightclub, the Red Fox, near Pennsylvania Avenue and Fulton Street in West Baltimore. As soon as he heard Ennis, he decided she was the singer that could establish the club as a destination venue.

“The Red Fox was a tiny place,” she recalls. “Maybe you could squeeze a hundred people in there. There was an island bar in the middle and a small stage in the corner; the wallpaper had cartoon animals prancing between cocktail glasses. But it was one of the few places in Baltimore where blacks and whites could come together comfortably. A lot of Hopkins students came, and so did a lot of gays. The music we did wasn’t low-down-and-dirty blues—it was jazz and pop tunes done in a jazz style.”

Fox became her manager and soon wrangled a recording deal with Jubilee Records in New York. Featuring pianist Hank Jones and drummer Kenny Clarke, Ethel Ennis Sings Lullabys for Losers was released in 1955 and caught some important ears.

“I had heard that Billie Holiday had asked one of her friends, ‘Who’s this new bitch from Baltimore?’” Ennis says. “Then one night, when I’m sleeping in my bed on Druid Hill, the phone rings at 3 in the morning and it’s Shery Baker, this hairdresser I knew in Baltimore. Shery says, ‘I’m in New York and I’ve got Billie Holiday on the line.’ I say, ‘Yeah, right,’ and hand the phone to my husband. He says, ‘It really is Billie Holiday,’ and hands me back the phone.”

At this point Ennis mimes her own groggy sleepiness and then impersonates Holiday’s famous rasp. “‘I like your voice,’” Holiday told her. “‘You’re a musician’s musician—you don’t fake. Stay with it and you’ll be famous.’” Ennis giggles, and then adds, “I thought that was strange, because I had never even thought about becoming famous.”

Fame would soon find Ennis. The Jubilee disc led to two albums with Capitol, 1957’s Change of Scenery and 1958’s Have You Forgotten? Benny Goodman, who had played on Holiday’s first recording, hired Ennis as his female singer (Jimmy Rushing was the male singer) for a 1958 tour of Europe. Ella Fitzgerald cited Ennis as her favorite young singer, and the voters in the Playboy Jazz Poll named Ennis the Best Female Singer of 1961.

In 1964-’65, Ennis released four full-length albums for RCA, played the Newport Jazz Festival with the Billy Taylor Trio, sang with the Duke Ellington Orchestra on network TV, and began a seven-year run on television’s Arthur Godfrey Show. Forty years ago Ennis was on the cusp of fame; she could have been another Nancy Wilson or Leslie Uggams, a silky-voiced chanteuse who straddled the boundary between jazz and adult pop. Ennis never quite got over that last hump, and she has been explaining why ever since.

There were several factors. The 1964 British Invasion led by the Beatles upended the music industry and drastically shrank the market for jazz and adult pop. Unlike Wilson and Uggams, Ennis looked nothing like Doris Day. While the Baltimorean’s unconventional looks are quite striking, they were not easy to market in 1964. Nor was it easy to market her unconventional approach to singing—her tendency to slow down tempos and to inject a playful humor into “America’s Classical Music.” The very things that made her music so interesting made it hard to sell.

“Audiences expect one thing,” she says, “and if they get another, they’re disappointed. Instead of seeing what’s there, they insist on what they expected. Jazz purists especially have a set idea of what jazz should be, but I always thought jazz was about freedom from rules. If I express myself through my music and I’m a playful person, then my music will be playful. People would criticize Dizzy Gillespie for the same thing, and I think that’s why he never got as much credit as Charlie Parker. But that’s what I like about Dizzy.

“People would tell me, ‘Ethel, you’re not serious enough, you’re not trying hard enough.’ And I’d reply, ‘Like the song says, “I got to be me—what else can I be?”’ I always try to find the humor in everything. After I divorced my first husband, I joked, ‘Loving you made me a better woman . . . for another man.’”

There were other reasons. Ennis refused to relocate from Baltimore to New York and thus never became an industry insider. That was part of her unwillingness to play by the rules of the mid-‘60s music biz.

“They had it all planned out for me,” she explains. “Go here and have your picture taken. Go to a choreographer—that was a disaster. Go to the right parties. ‘When do I sing?’ I’d ask. ‘Shut up and have a drink.’ You should sit like this and look like that and play the game of bed partners. You really have to do things that go against your grain for gain. I wouldn’t.”

After her RCA contract ran out, she came back to her rowhouse in Mondawmin and went back to singing at the Red Fox with occasional forays out of town. Everyone around her was worried that she was throwing away her career, but Ennis wasn’t worried. She was paying her bills and singing what she wanted. She never approached the mythic status of Holiday, but neither did Ennis endure Holiday’s drug problems or abusive relationships.

At this time a young Sun reporter, Earl Arnett, was in the habit of stopping by the Red Fox after work. He wondered why such a major talent as Ennis was singing in a 100-seat club on Pennsylvania Avenue and convinced his editor to assign a story to answer that question. Arnett, came to Ennis’ rowhouse for an interview in March 1967, but instead of writing the story he started dating her. They were married that August.

Happily married, Ennis was content to become a local legend rather than an international star. Though she continued to travel now and then to the West Coast, other East Coast cities, and Europe, she became a fixture at the King of France Tavern in Annapolis and at public festivals in Baltimore. Whenever Maryland politicians such as William Donald Schaefer or Spiro Agnew wanted to showcase local artists, they would turn the spotlight on Ennis.

She and her husband were partners in the jazz club called Ethel’s Place that was in the Theatre Project building from 1985 through 1988. Since they were bought out by Washington’s Blues Alley (which only lasted a year in the Mount Vernon space), Ennis has taken it easy. She plays less than 20 dates each year and releases an album about every five years (1994’s Ethel Ennis on Hildner, 1998’s If Women Ruled the World on Savoy, and the new Ennis Anyone? Ethel Ennis Live at Montpelier on Jazzmont). Next March she takes part in pianist Bill Charlap’s tribute to Vernon Duke at New York’s Lincoln Center. That’s enough for her.

“I don’t like the way the music business is set up,” she insists. “You have to give up a whole lot for that prize, and it isn’t worth it. It’s not like they’re going to nurture the individuality of your talent—they’re going to fit you into a slot they already have. It didn’t appeal to me, and it still doesn’t. So I took a step back to think about it. Meanwhile, they said, ‘Next.’

“I have no regrets. I’d do the same thing again. I’m trying to respect the gift I do have and not worry about the prize. There’s a difference between ambition and determination: Ambition is when you’ll do whatever they ask, determination is when you’ll do what you want no matter what.”

When she sings her own composition, “Hey You,” on Ennis Anyone?, she introduces it with a monologue. “I did ask myself the question many years ago, ‘Ethel, are you doing what you want to do?’ The answer is still, ‘Yes.’ That’s why I feel that I can ask you, ‘Are you doing what you want to do?’ Because we come here with two pieces of paper—birth certificate, death certificate—and it’s up to us to figure what we’re going to do between those two slips of paper.”

The song itself is a sassy blues with a finger-snapping beat from the trio of Scaggiari, bassist Mark Russell, and drummer Ryan Diehl. Ennis good-naturedly jabs the question at the audience: “Hey, you, are you doing what you want to do?” Back at her rowhouse, she explains that she wrote the song after her grandmother died in 1977.

“When I came home from the funeral,” Ennis recalls, “I listened to B.B King’s ‘The Thrill Is Gone.’ That gave me the feel I wanted, and I got real quiet and went inside myself to let the words come. I remembered all my grandmother’s teachings, how she used to talk about the Bible like those people were her neighbors. That’s how I came up with that line, ‘Are you doing what you want to do?’ I have talked to so many people who are not doing what they want, and they sicken themselves as a result. I’m trying to pull people’s coattails: Don’t put it off till later. You might die before you do what you want to do.”

You can read the Baltimore City Paper Online HERE.

Here is a video of Ethel Ennis singing "I've got that feeling"

Here is a video of Ethel Ennis singing "I've got that feeling"

Download the video HERE.

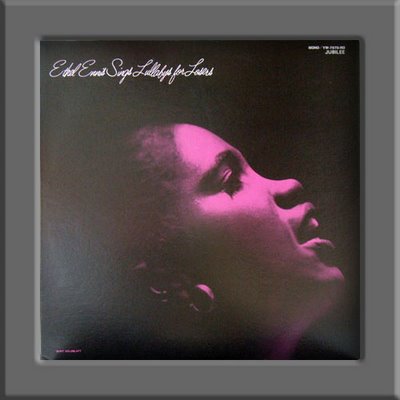

Left, original Jubilee cover art. Right, second Jubilee cover art with a white Ethel !!!

Ennis debut LP "Lullabies for Losers" appeared on Jubilee in 1955, with the follow-up, "Change of Scenery", issued two years later on Capitol; around the same time, she toured Europe with Benny Goodman, but finding the grind of the road too intense she returned home to Baltimore, and -much to the detriment of her rising fame- rarely played outside of the Charm City area in the decades to come. After 1958's "Have You Forgotten?", Ennis did not resurface until six years later, landing at RCA for "This Is Ethel Ennis"; three more LPs -"Once Again", "Eyes for You" and "My Kind of Waltztime"- quickly followed before another eight-year studio hiatus which finally ended with the 1973 release of the BASF album "10 Sides of Ethel Ennis". Ennis next turned up on vinyl in 1980 with "Live at Maryland Inn".In 1982, Mayor William Donald Schaefer appointed both Ennis and her husband, Earl Arnett, Cultural Ambassadors of the City of Baltimore. This honor would eventually take her, in 1987, to the First International Music Festival in Xiamen, China. Despite international acclaim and worldwide tours, Ennis has been able to avoid the trials and tribulations of fame by remaining in her hometown of Baltimore. Some critics cite this as a fault, but Ennis defends her choices in a biography entitled "Ethel Ennis: The Reluctant Jazz Star", written by Sallie Kravetz in 1984.

Remaining in Baltimore has enabled Ennis to take an active role in civic duties. She was nominated to the Hall of Fame of Frederick Douglass High School and received an honorary Doctor of Fine Arts Degree from the Maryland Institute College of Arts.

In recent years, Ennis has become involved in the award-winning children's program produced by the Maryland Department of Instructional Television called "Book, Look, and Listen" In 1984, Ennis opened "Ethel's Place" - her own music club located in Baltimore's cultural district across from the Meyerhoff Symphony Hall. A great success, the club actually broadcast live on public television across the country on New Year's Eve in both 1985 and 1987. Ethel performed with Joe Williams, Ray Brown and Milt Jackson, Phil Woods, Gerry Mulligan, Toots Thielemans, Wynton Marsalis, McCoy Turner, and Stephane Grappelli in these memorable broadcasts. In 1988, Ennis and her husband Arnett, made the difficult decision to sell "Ethel's Place" in order to "devote their creative energies to words and music." Ennis has survived and overcome many prejudices as a black woman, both in her professional and personal life. She uses her music as a weapon to combat prejudice and injustice throughout the world, by promoting love, compassion, and unity. Ennis refers to this power as "Soft Power", a "power within, the spiritual energy we all possess to change ourselves and the world around us." In this way, she believes music is not only a medium to be used for entertainment, but also a way to "inform and inspire."

A Hildner Productions cd "Ethel Ennis" came out in 1993. It celebrates Ethel’s first major recording in over 14 years. It consists of 11 jazz standard and contemporary songs in an exquisite chamber music style that highlights the musicality and phrasing that has made Ethel one of the luminary singers of our time. Ethel is accompanied by jazz master musicians Marc Copland and Stefan Scaggiari trading off on piano, Drew Gress on bass, and Paul Hildner on drums. Ethel shows her versatility and brilliance by accompanying herself on piano for the much loved hit “Something Cool.” Then came "If Women Ruled the World" in 1998.

The is the first Ethel Ennis lp (mono recording) and you shouldn't miss it. At this time Ethel Ennis is only 23 years old !!! A wonderful voice capably backed by Hank Jones piano, Abie Baker bass, Eddie Biggs guitar and Kenny Clarke drums. (The lp is 50 years old... but plays very well)

ETHEL ENNIS SINGS LULLABYS FOR LOVERS 1955 LP

Here, Geoffrey Himes from the Baltimore City Paper, tells us Ethel Ennis story...

At the end of her new cd "Ennis anyone?", Ethel Ennis tackles the old jazz standard “But Beautiful.” As is her wont, the Baltimore singer slows the tempo, even slower than the famous ballad versions by Nat King Cole, Bill Evans, and Billie Holiday. In her still-lustrous soprano, Ennis stretches out the melody and lyrics as if they were taffy, capturing the wistful realization that, even when it tortures us, love is beautiful in its way.

At the end of her new cd "Ennis anyone?", Ethel Ennis tackles the old jazz standard “But Beautiful.” As is her wont, the Baltimore singer slows the tempo, even slower than the famous ballad versions by Nat King Cole, Bill Evans, and Billie Holiday. In her still-lustrous soprano, Ennis stretches out the melody and lyrics as if they were taffy, capturing the wistful realization that, even when it tortures us, love is beautiful in its way.But Ennis can’t stay serious for long. After Stef Scaggiari’s elegant piano solo, she murmurs, “As Billie would sing,” and launches into a spot-on impersonation of Holiday, full of throat-scraping purrs, that has the live audience at the Montpelier Cultural Arts Center in Laurel chuckling.

It’s a telling moment, for Ennis is probably the second most famous jazz singer to come from Baltimore. Ennis’ fame falls far short of Holiday’s, but the local legend has had a much longer and much more contented life than the international legend did, and that’s a trade-off Ennis is glad she made.

Ennis will forever be tied to Holiday by their shared hometown. But when she’s singing in her own voice, Ennis doesn’t sound all that much like Holiday. Ennis’ rounded, flush tone and bouncy phrasing more closely resemble her two biggest heroes, Sarah Vaughan and Ella Fitzgerald. And Ennis’ playfulness—her habit of breaking into impersonations, new comic verses, or impromptu patter in the middle of a song—is the diametric opposite of Holiday’s troubled-martyr persona. That playfulness may have cost Ennis a Holiday-like myth, but it has helped keep her sane.

“It bothers some people if an artist is just like them,” Ennis muses. “They don’t want Ethel the neighbor—they want Ethel the diva. They want their artists to be off in the distance somewhere on a pedestal. I never wanted to be on a pedestal. There’s not enough room to move around.

“I was never as famous as Billie, but I’ve definitely had a happier life, and I credit that to my grandmother and her teachings,” she continues. “I credit it to the musicians I worked with, because they took care of me; they didn’t take advantage of me. And I credit it to never leaving Baltimore to move to New York, even though people kept telling me I should. I’ve always believed you can bloom where you’re planted. You may not get wealthy or famous, but you can bloom.”

Ennis, now 72, grins broadly as she slouches on the couch in her brick rowhouse near Mondawmin Mall. Her hair is cropped close in a salt-and-pepper Afro; she wears a white sweater and black slacks and sports two diamond studs in each ear. Next to her on the couch is her husband, Earl Arnett, the former Sun reporter who defied Maryland’s miscegenation laws at the time to marry the young singer in 1967. They’ve lived in this same house ever since.

Not far from that house is the Gilmor Homes public housing project in Sandtown-Winchester, where Ennis grew up. In the 1930s and ’40s, when she lived there, housing projects were brand new and desirable. It was a tight-knit village, a breeding ground for such musicians as guitarist O’Donel Levy, keyboardist Charles Covington, and drummer Chester Thompson. Ennis herself took piano lessons so she could play at the Ames United Methodist Church when her mother had to take some time off.

“But we lived above a lady who threw house parties on weekends with red and blue lights,” Ennis remembers. “My grandmother thought it was terrible, but the music would come up through the floorboards from the apartment below, and I could really hear the bass lines. I remember hearing Lil Green singing, and that’s how I learned the blues.”

The Abraham Riley Octet, a bebop band in the Gilmor Homes, needed a pianist and invited the 15-year-old Ennis to join the band. One night at a Randallstown Odd Fellows Hall, with a stove in the middle of the floor, a customer offered Riley a big tip if Ennis would sing Lil Green’s “Romance in the Dark.” She had never sung in public before, not even in church, but the tip was too big to resist. She was only 15 and could only guess at what the suggestive lyrics hinted at, but a big, vibrant soprano that she never knew she had came pouring out of her mouth. The crowd went nuts, and she had to sing it again and again.

Soon she was singing all over town, eventually as a piano-and-bass duo with Montell Poulson. They played the Casino across from the Royal Theatre, Sherrie’s Bar in Highlandtown, the Zanzibar in West Baltimore, Phil’s in East Baltimore, and even the Oasis and the Flamingo strip clubs on the Block. Then she met George Fox, a short, round, 300-pound cannonball of a man who was literally a Damon Runyon character: Runyon had written about Fox’s exploits as a Times Square gambler in Manhattan.

After leaving Manhattan under shady circumstances, Fox ended up with a nightclub, the Red Fox, near Pennsylvania Avenue and Fulton Street in West Baltimore. As soon as he heard Ennis, he decided she was the singer that could establish the club as a destination venue.

“The Red Fox was a tiny place,” she recalls. “Maybe you could squeeze a hundred people in there. There was an island bar in the middle and a small stage in the corner; the wallpaper had cartoon animals prancing between cocktail glasses. But it was one of the few places in Baltimore where blacks and whites could come together comfortably. A lot of Hopkins students came, and so did a lot of gays. The music we did wasn’t low-down-and-dirty blues—it was jazz and pop tunes done in a jazz style.”

Fox became her manager and soon wrangled a recording deal with Jubilee Records in New York. Featuring pianist Hank Jones and drummer Kenny Clarke, Ethel Ennis Sings Lullabys for Losers was released in 1955 and caught some important ears.

“I had heard that Billie Holiday had asked one of her friends, ‘Who’s this new bitch from Baltimore?’” Ennis says. “Then one night, when I’m sleeping in my bed on Druid Hill, the phone rings at 3 in the morning and it’s Shery Baker, this hairdresser I knew in Baltimore. Shery says, ‘I’m in New York and I’ve got Billie Holiday on the line.’ I say, ‘Yeah, right,’ and hand the phone to my husband. He says, ‘It really is Billie Holiday,’ and hands me back the phone.”

At this point Ennis mimes her own groggy sleepiness and then impersonates Holiday’s famous rasp. “‘I like your voice,’” Holiday told her. “‘You’re a musician’s musician—you don’t fake. Stay with it and you’ll be famous.’” Ennis giggles, and then adds, “I thought that was strange, because I had never even thought about becoming famous.”

Fame would soon find Ennis. The Jubilee disc led to two albums with Capitol, 1957’s Change of Scenery and 1958’s Have You Forgotten? Benny Goodman, who had played on Holiday’s first recording, hired Ennis as his female singer (Jimmy Rushing was the male singer) for a 1958 tour of Europe. Ella Fitzgerald cited Ennis as her favorite young singer, and the voters in the Playboy Jazz Poll named Ennis the Best Female Singer of 1961.

In 1964-’65, Ennis released four full-length albums for RCA, played the Newport Jazz Festival with the Billy Taylor Trio, sang with the Duke Ellington Orchestra on network TV, and began a seven-year run on television’s Arthur Godfrey Show. Forty years ago Ennis was on the cusp of fame; she could have been another Nancy Wilson or Leslie Uggams, a silky-voiced chanteuse who straddled the boundary between jazz and adult pop. Ennis never quite got over that last hump, and she has been explaining why ever since.

There were several factors. The 1964 British Invasion led by the Beatles upended the music industry and drastically shrank the market for jazz and adult pop. Unlike Wilson and Uggams, Ennis looked nothing like Doris Day. While the Baltimorean’s unconventional looks are quite striking, they were not easy to market in 1964. Nor was it easy to market her unconventional approach to singing—her tendency to slow down tempos and to inject a playful humor into “America’s Classical Music.” The very things that made her music so interesting made it hard to sell.

“Audiences expect one thing,” she says, “and if they get another, they’re disappointed. Instead of seeing what’s there, they insist on what they expected. Jazz purists especially have a set idea of what jazz should be, but I always thought jazz was about freedom from rules. If I express myself through my music and I’m a playful person, then my music will be playful. People would criticize Dizzy Gillespie for the same thing, and I think that’s why he never got as much credit as Charlie Parker. But that’s what I like about Dizzy.

“People would tell me, ‘Ethel, you’re not serious enough, you’re not trying hard enough.’ And I’d reply, ‘Like the song says, “I got to be me—what else can I be?”’ I always try to find the humor in everything. After I divorced my first husband, I joked, ‘Loving you made me a better woman . . . for another man.’”

There were other reasons. Ennis refused to relocate from Baltimore to New York and thus never became an industry insider. That was part of her unwillingness to play by the rules of the mid-‘60s music biz.

“They had it all planned out for me,” she explains. “Go here and have your picture taken. Go to a choreographer—that was a disaster. Go to the right parties. ‘When do I sing?’ I’d ask. ‘Shut up and have a drink.’ You should sit like this and look like that and play the game of bed partners. You really have to do things that go against your grain for gain. I wouldn’t.”

After her RCA contract ran out, she came back to her rowhouse in Mondawmin and went back to singing at the Red Fox with occasional forays out of town. Everyone around her was worried that she was throwing away her career, but Ennis wasn’t worried. She was paying her bills and singing what she wanted. She never approached the mythic status of Holiday, but neither did Ennis endure Holiday’s drug problems or abusive relationships.

At this time a young Sun reporter, Earl Arnett, was in the habit of stopping by the Red Fox after work. He wondered why such a major talent as Ennis was singing in a 100-seat club on Pennsylvania Avenue and convinced his editor to assign a story to answer that question. Arnett, came to Ennis’ rowhouse for an interview in March 1967, but instead of writing the story he started dating her. They were married that August.

Happily married, Ennis was content to become a local legend rather than an international star. Though she continued to travel now and then to the West Coast, other East Coast cities, and Europe, she became a fixture at the King of France Tavern in Annapolis and at public festivals in Baltimore. Whenever Maryland politicians such as William Donald Schaefer or Spiro Agnew wanted to showcase local artists, they would turn the spotlight on Ennis.

She and her husband were partners in the jazz club called Ethel’s Place that was in the Theatre Project building from 1985 through 1988. Since they were bought out by Washington’s Blues Alley (which only lasted a year in the Mount Vernon space), Ennis has taken it easy. She plays less than 20 dates each year and releases an album about every five years (1994’s Ethel Ennis on Hildner, 1998’s If Women Ruled the World on Savoy, and the new Ennis Anyone? Ethel Ennis Live at Montpelier on Jazzmont). Next March she takes part in pianist Bill Charlap’s tribute to Vernon Duke at New York’s Lincoln Center. That’s enough for her.

“I don’t like the way the music business is set up,” she insists. “You have to give up a whole lot for that prize, and it isn’t worth it. It’s not like they’re going to nurture the individuality of your talent—they’re going to fit you into a slot they already have. It didn’t appeal to me, and it still doesn’t. So I took a step back to think about it. Meanwhile, they said, ‘Next.’

“I have no regrets. I’d do the same thing again. I’m trying to respect the gift I do have and not worry about the prize. There’s a difference between ambition and determination: Ambition is when you’ll do whatever they ask, determination is when you’ll do what you want no matter what.”

When she sings her own composition, “Hey You,” on Ennis Anyone?, she introduces it with a monologue. “I did ask myself the question many years ago, ‘Ethel, are you doing what you want to do?’ The answer is still, ‘Yes.’ That’s why I feel that I can ask you, ‘Are you doing what you want to do?’ Because we come here with two pieces of paper—birth certificate, death certificate—and it’s up to us to figure what we’re going to do between those two slips of paper.”

The song itself is a sassy blues with a finger-snapping beat from the trio of Scaggiari, bassist Mark Russell, and drummer Ryan Diehl. Ennis good-naturedly jabs the question at the audience: “Hey, you, are you doing what you want to do?” Back at her rowhouse, she explains that she wrote the song after her grandmother died in 1977.

“When I came home from the funeral,” Ennis recalls, “I listened to B.B King’s ‘The Thrill Is Gone.’ That gave me the feel I wanted, and I got real quiet and went inside myself to let the words come. I remembered all my grandmother’s teachings, how she used to talk about the Bible like those people were her neighbors. That’s how I came up with that line, ‘Are you doing what you want to do?’ I have talked to so many people who are not doing what they want, and they sicken themselves as a result. I’m trying to pull people’s coattails: Don’t put it off till later. You might die before you do what you want to do.”

Here is a video of Ethel Ennis singing "I've got that feeling"

Here is a video of Ethel Ennis singing "I've got that feeling"Download the video HERE.

3 comments:

Incredible voice! Thanks so much for the introduction. I can't wait to listen to the other artists you suggested.

meltingplastic

Never heard of this singer but I really liked Lullabys For Losers . Nice after-hours mood with interesting , uncommon material sung in a way that conveys the emotion behind the lyrics .

Can't imagine where I would have heard this other than on this blog . Thanks !

PATRICIA, YOU'LL SOON GET REALLY HOOKED WITH THE VOICES TOO... BEST. DANIEL

Post a Comment